It’s December 7th, and for most of us it’s just another day. But for my grandpa Bill, my mom’s father, it is “a day which will live in infamy.” This is how President Franklin D. Roosevelt described the day on which Japanese planes bombed Pearl Harbor on a quiet Sunday morning in 1941.

Recently, I interviewed my grandpa, whom I call Gung Gung (“Grandpa” in Cantonese), to document his experiences that day and the months that followed. Our conversation was a helpful part of my reschooling: unlike many of my history classes, it was meaningful, story-based, and personally relevant. It also helped me appreciate the value of hard work and security. Here is an excerpt of the piece.

***

These are some things that my grandpa Bill likes: A $1.99 roast beef sandwich at Arby’s. The plastic forks that he keeps in a kitchen drawer, just in case. The cup of coffee at McDonald’s he gets each day with his senior citizen discount. He has always provided well for me and the rest of his family, and at the same time, nothing makes him smile like a good deal.

My mom’s father is a triple threat of thriftiness: he’s a senior citizen, he’s Chinese (a culture known for being frugal) and he came of age in Depression-era Hawaii. It wasn’t until I interviewed him about a major event in his life that I understood the roots of his “waste not, want not” values.

In December 1941, my grandpa was living in Hawaii, seven miles from Pearl Harbor on the morning it was bombed. This is his story.

***

One early Sunday morning after church, Bill was eating breakfast by himself in his family’s modest dining room when he heard loud noises outside. They came sporadically and sounded like cannon fire. He didn’t pay much attention at first, because the military bases nearby would often fire cannons in practice drills called “maneuvers.” Bill, a 17-year-old high school student known for his slick black hair and big smile, kept on eating.

As the thundering sounds continued, it occurred to Bill that they were abnormally loud, and that one came quickly after the other. He realized that the cannons never fired practice rounds that early on a Sunday morning. When the sounds kept coming, he knew that something was wrong. He gobbled down the rest of his food, jumped up, and ran out the front door and down the porch steps to see what was happening.

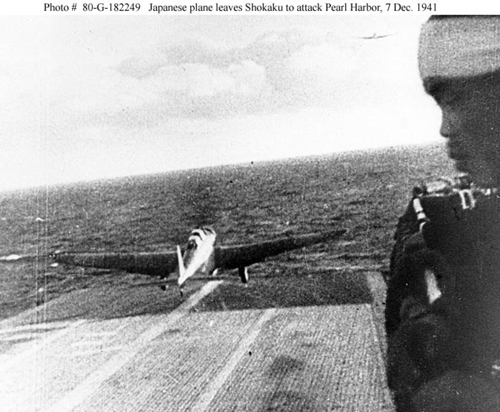

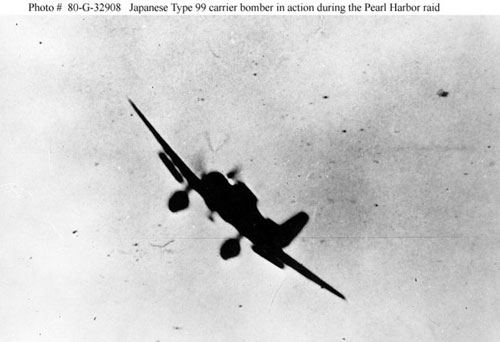

The date was December 7, 1941. What Bill had heard were bombs that Japanese planes had dropped over Pearl Harbor, and U.S. cannons firing back at them. The attack had taken Hawaii—and the rest of America—completely by surprise.

The cannon fire continued as Bill dashed down his front steps and out into the street to investigate. People were beginning to run out of the open doors of their homes, stepping outside their picket fences to look up at the sky. Some looked half-asleep, having been awakened by loud noises. They seemed more curious than afraid, looking toward the horizon for an explanation. Bill and his neighbors could see black smoke billowing up to the sky from the direction of Pearl Harbor.

Soon, the neighbors who had radios in their homes came outside to share the news with their neighbors: The Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbor. They had sunk the USS Arizona, a Navy battleship, and killed an untold number of service members.

“This is not a drill,” the radio announcer said. “This is the Real McCoy. Take cover.”

***

Within hours after the bombings, the open-door culture of Oahu had changed completely. The U.S. suspected that Japan might attack Hawaii again, so the local Civil Defense department ordered what they called “blackout” every night until further notice. According to the rationale, if the islands went dark at night, Japanese planes would have difficulty finding them from the air. If families wanted to use their lights after dark, they had to black out their windows.

Starting at nightfall, the only people allowed in the streets were military officers — whom Bill and his neighbors called “wardens” – who would patrol the streets and knock on doors of houses showing even the tiniest bit of light. If you didn’t comply with their requests, Bill says, you could face military court or go to jail.

Because the people in Bill’s Honolulu neighborhood normally left all the doors and windows open, day and night, the blackout made for a significant change in their lifestyle. Still, no one complained about suddenly being closed off from each other.

“Everybody was in the same situation,” Bill says. “We just obeyed the law and that was it. I don’t think people were upset about it, because it was for our own good.”

Because of fears of a gas attack, Hawaiian residents each had to carry a military-issue gas mask at all times. Bill waited in line at one of the neighborhood stations set up to hand out masks. You didn’t need an appointment, he says, you just walked through and picked one up.

The gas mask fit over the face and made you look “just like an alien,” according to Bill. It connected to the tin canister with a tube. The sack weighed about two pounds, which Bill didn’t find heavy. He carried it on his back, to school and home. While he was sleeping, he put it on a chair nearby, where he could get to it quickly if necessary.

Schools held drills so that students could practice putting on their masks quickly. One drill involved filling a room with tear gas. Each student would practice entering the room and putting on their mask as quickly as possible. If they couldn’t do it quickly, their eyes would fill with tears and they would begin coughing. Bill says that this experience was so uncomfortable that if it happened to you, you made sure to learn how to put your mask on correctly, and fast.

***

Hawaii continued under martial law for three years, until the fall of 1944. Schools and families dug small trenches in their front yards in case of another bombing. The government rationed foods like sugar and red meat to divert more to the soldiers. Friends and family were drafted for the military, including three of Bill’s four brothers. In 1945, word spread that the war had finally ended. The troops — including Bill’s brothers — were beginning to come home.

***

Today, at age 86, my grandpa Bill takes a matter-of-fact attitude toward everything in his life, including the events of Pearl Harbor. He doesn’t acknowledge any emotional impact from the bombings or the nearly three years of martial law in Hawaii. He doesn’t think about the bombing much because it was 69 years ago.

However, every December 7th, he wakes up remembering the 2,400 people who died in the bombing. He’s disappointed with the news coverage, because as time passes, he sees less and less about Pearl Harbor.

“Every year,” he says, “there’s not anything in the newspaper anymore, a two-inch write-up and that’s it. No news articles, no TV, nothing.”

“I think they should remember those people who died at Pearl Harbor,” Bill says about the media. “The younger generation doesn’t know what happened. Except those who (were) there, yeah, they remember.”

In 1953, eight years after the war ended, my grandpa Bill moved to the Washington, D.C. area for a stable job with the federal government. He stayed with it for over 30 years. Now, although he has a comfortable monthly pension, he is still one of the most frugal people I know. He eschews luxuries in favor of practical expenses, like the education of his grandchildren.

I look at my grandpa Bill today, reading The Washington Post in his armchair and keeping an eye out for coupons for Kentucky Fried Chicken, and I think about how different our generations are. Many of my peers and I grew up with every opportunity, so our happiness lies in living out adventurous dreams of travel, and entrepreneurship – in other words, the unpredictable.

My grandpa’s generation, on the other hand, never even felt entitled to happiness, like mine did. He and his peers grew up in a culture of uncertainty that they would make it through the night without incident, or have enough to eat the next day. He’s lived through bombings, gas masks, rationing, and blackouts, things that my generation would find unbearable.

My grandpa worked hard for years to survive tough times, then built a stable life for his family over several decades. Now that they are safe and well fed, the unpredictable is the last thing that he wants. He knows what to expect tomorrow, and the day after that. For my grandpa Bill, these simple assurances are what he has worked so hard to gain.

See the Huffington Post’s coverage of today’s gathering of survivors in Pearl Harbor.

Thanks for writing this, Melia. I’ve never heard Gung Gung say much about the bombing of Pearl Harbor besides the very basic facts, and this is a really interesting and well-written account.

We just moved away from Hawaii before this year’s anniversary, but we were there last year, and it is still pretty important on Oahu. I think everyone — military and civilian alike — tries to remember and honor those who died at Pearl Harbor. It’s harder to forget because the USS Arizona is right there as a constant reminder.

Thanks, Gill. It definitely took some effort to get Gung Gung to give so much detail. What struck me was how matter-of-fact he was about all the wartime inconveniences, like blacking out the windows and carrying gas masks everywhere. It was a time when everyone banded together for the country without complaint, and I admire that a lot.

I’m glad to hear that Pearl Harbor Day is still so important on Oahu, to both military folks and civilians. I hope to make it back there one day soon so I can go to the expanded visitors’ center.

I echo the thanks – well written and touching. In fact, on 12/7 this year I had my own “isn’t this Pearl Harbor day?” thought, but didn’t hear much about it. With military service in my family and several friends who served, I did take a moment and will continue to share the story as I too believe it’s an important one to tell. Thanks!

This is a wonderfully composed recollection of a born in the depression era Gung Gung by his modern 28-year old granddaughter, written with respect and love and even some humor, quite touching. Anyone who’d disagree should have their head examined! Suggest Melia expand this into book form, too.

Laura and Janet, thanks for the comments. Since my grandpa mentioned that news coverage of Pearl Harbor Day has faded, I look for it every December 7th. Thanks for reading Gung Gung’s story; I know he’ll be pleased.

This is a great article about what we can learn from our elders as I am also blessed to have a 94 year old mother who shares her interesting life stories with us including those about the war. Your grandparents must be very proud of you.

The writing about your grandfather was quite interesting. There are fewer and fewer people around who actually lived through that part of our American history. It is good to keep their memories written so others will know about the experiences during that time.